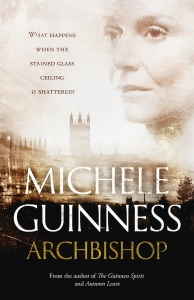

Today I received the paperback edition of Michele Guinness’ page-turning, magisterial novel, Archbishop, in which she explores the issues facing women in leadership. For your reading pleasure, here’s an interview with her, originally published in Woman Alive.

When my husband and I were at theological college, we met so many strong women, many of whom have gone on to great things – they became deans and archdeacons. I suddenly thought, What would it be like to have a woman archbishop? Would it be different? What would be the pressures for a woman, especially a woman leader at a time where not everyone is reconciled to the idea?

When my husband and I were at theological college, we met so many strong women, many of whom have gone on to great things – they became deans and archdeacons. I suddenly thought, What would it be like to have a woman archbishop? Would it be different? What would be the pressures for a woman, especially a woman leader at a time where not everyone is reconciled to the idea?

When at theological college, I was very agnostic about the role of women in the church – I hadn’t thought it through. And then I met these women who were just extraordinary and exceptional, and a part of me said, how can their calling be wrong? So I looked at all the biblical stuff on women, and particularly Romans 16, in Paul’s closing words to the Romans from prison. He mentions the women who have worked by his side, and he uses the same words for them in the Greek as for Timothy and Silas and the big guns. He entrusts the letter to Phoebe, who is his patron, and who runs the church in Cenchreae, and I thought at that point, yes, it’s okay, these women are not mistaken or misled. I became convinced that women have a very special role.

We have to look very carefully at how women lead; it’s not easy for women in leadership to maintain their femininity, vulnerability or integrity. So I wanted to create somebody who had a go! I wanted to explore where would it take her, and what would it cost her. What difference can we women make in society today? Can we have a voice?

Yet a lot of women who become powerful pull the ladder up: they don’t encourage younger women to look for their potential. So I wanted to create a woman who wasn’t like that; rather someone who was confident and secure in who she was; someone who would say, this is who I am and this is all I have to give and if I have to pay for it, so be it.

I’m aware that people can see the weaknesses of Vicky, my archbishop; she has frailties, for she’s very human. She also has this wonderful spiritual director who helps her to keep on the straight and narrow. And I realized that those who might be against women in leadership could use her weaknesses as a weapon to say that women aren’t up to it. So I tried to create someone who had a lot of integrity, honesty and vulnerability. We need that in church leadership, whether it’s male or female.

We haven’t seen many very public and powerful women leaders who can maintain that femininity. But I wanted to have someone who was out of the political scene, and yet could become a figurehead for women. She’d have to be tough and feisty enough to get where she got, but at the same time able to maintain her femininity. At one point in the book she says to herself, “Don’t cry. Be a man.” Nor does she use her tears manipulatively.

When Vicky became archbishop she had to have a vision. We all have to have a vision; whether we live up to it is another matter. But if you don’t have a vision, you won’t even start. And so she had to have a sense of the objectives she wanted to achieve. I’ve left it a bit like-life, that with some of them she gets a long way down the road and some of them she doesn’t and has to leave them for the future. That’s true of all of our lives; there will be things that we had planned to do that we do, and a lot of things that we don’t, which we leave to the next generation.

That’s coping with loss. As you get older, you realize that there are still a lot of things that you haven’t done and that you don’t have a lot of time left to do them. And that an awful lot of things you need to inspire the next generation to do. Vicky does that through her preaching. When she gets up and preaches, young people like to listen to her, as do old people and people who’ve got no faith.

One person observed that there were a lot of very dark forces at play in the novel; surely this doesn’t happen in the church. I had to say that actually it does. We’ve experienced it. And I had insider information; someone very close to the centre. He wrote me huge notes about how emotion in Synod sounds: No, you couldn’t say that; no, she wouldn’t do that. It was brilliant; I was so grateful.

One person observed that there were a lot of very dark forces at play in the novel; surely this doesn’t happen in the church. I had to say that actually it does. We’ve experienced it. And I had insider information; someone very close to the centre. He wrote me huge notes about how emotion in Synod sounds: No, you couldn’t say that; no, she wouldn’t do that. It was brilliant; I was so grateful.

I can envision a world where certainly here in the UK, being a Christian is less acceptable, where the secularists move into the ascendancy. It has started and continues, but my hope is that if something like an Anti-Proselytizing Law comes into effect, that actually will make people want to know what about Christianity is so offensive. I can foresee as well that in times of persecution, the church is at its best. My publisher was really hot on this, for he said that people in society just don’t know what Christians do, and how much voluntary work would grind to a halt without them.

Peter and I were like ships that passed in the night when I worked as a senior manager in the NHS. And neither of us particularly enjoyed that, much as I loved my job and he loved his. We could only sustain it for a number of years; I think we did it for 5 years in the end. After that, although he encouraged me to continue, I felt that I needed to give up. It was a hard decision, but looking back, it was the right one.

In the case of the novel, it’s Tom, Vicky’s husband, who gave up as an NHS consultant. It’s a very big question for couples. It’s very hard when you have children, and childcare is a real issue. And you think to yourself, once they’ve gone, now we can both really go for it. That’s what Peter and I did, and what you don’t realize you’re doing is compensating for the loss of the children – you’re grieving. Peter threw himself into his work, because the children make you stop. Children give you a reason to stop. And neither of us had that anymore.

In the early days of your marriage when you’re both working and you have childcare to sort out, it’s very tricky, and then later in life, you think it’s going to get easier. But if you both have high-powered careers, or hugely demanding careers, you face different battles – but battles. I’m not saying that couples can’t do it, and I take my hat off to those who do, but marriage is about giving to each other. If you’re both going to have high-powered careers, at one moment, one will take priority and the other will have to give way, and at other times the other will take priority. If you don’t have that understanding, I don’t see how you can do it.

The press, particularly the tabloid press, will pick on aspects of the physical side of women – how they look and come across – in a way that they’d never done with men. I think the first woman bishop will have quite a battle on her hands. Everything from the timbre of her voice to whether she wears makeup to the length of her skirt – everything will be up for grabs, especially in the tabloids, I have no doubt. And then it might then settle down. But women are treated differently than men. No one says of a bishop, “Oh, another middle-aged, balding bishop.” But they do look at whether or not a woman is attractive.

The press have a celebrity issue. They get tired of the idols they create and give them feet of clay. For a woman who is vulnerable and honest and open, she’s a really easy target. You look back at the way Mrs Thatcher was treated; the discussion of pearls and her blouses… The analysis of her shoes and hair and even her sexuality, how power gives women a certain attractiveness. The press talked about all of that in a way that they never talk of a male politician. And they still do the same way today – you never hear them mention David Cameron’s shoes!

This is hard on women. The first woman archbishop will need a good press manager who can handle this as well as possible. But even so, you can never manage the press completely; they really are a wild animal. I used to say that you can feed them, but you can’t tame them.

The other thing a woman archbishop would have to face is if she spoke out on issues of justice, how newspapers and many politicians would be saying that it’s not the role of the church to get involved in political issues.

The journalist in me uses a lot of fact. I found that the easiest bit, writing up something that was factual and fictionalizing it. It was very cathartic. There were some things in the novel that I could let go of once I’d written them, from churches we’ve been in, to situations we’ve experienced. The going out at night from the ordinand’s retreat looking for chocolate actually happened to Peter! You start with fact and then you let your imagination play.

The journalist in me uses a lot of fact. I found that the easiest bit, writing up something that was factual and fictionalizing it. It was very cathartic. There were some things in the novel that I could let go of once I’d written them, from churches we’ve been in, to situations we’ve experienced. The going out at night from the ordinand’s retreat looking for chocolate actually happened to Peter! You start with fact and then you let your imagination play.

I loved writing about the Queen. I sat down and thought, “I can’t do this; I can’t do this!” And then I kind of heard her voice in my head! Apparently she has a lot of humour and she’s very personable and I just went on what I knew. Writing about the Queen was such a fun thing to do. I hope she reads it!

Part of me as a writer that has always felt that other people are out there fighting for justice. My spiritual director said to me, “In the body of Christ there are many members, and you are a mouth.” And my daughter Abby said, “You’ve got it officially now, Mum; a mouth on legs!” It’s comforted me a little bit, but part of me would like to be the mouth that’s out there, fighting for justice and being the advocate that I haven’t been.

Some people say, “Is Vicky you?” She’s not. But there might be a part of me that would like to be her.

Leave a Reply